John Sumner of Birmingham publishes A Popular Treatise on Tea, which opens with an epigraph from the poem “Charity” by William Cowper:

“The bond of commerce was design’d

T’associate all the branches of mankind;

And if a boundless plenty be the robe,

Trade is the golden girdle of the globe…”

All right now. I went to buy a new hat yesterday and I said, “I’d like a new hat, please.” And so, they showed me a few hats, green ones and blue ones, and I didn’t like any of them, not one bit. What did I say? What did I just say?

DADDY

You didn’t like any of them, not one bit.

MOMMY

That’s right; you just keep paying attention. And then they showed me one that I did like. It was a lovely little hat, and I said, “Oh, this is a lovely little hat; I’ll take this hat; oh my, it’s lovely. What color is it?” And they said, “Why, this is beige; isn’t it a lovely little beige hat?” And I said, “Oh, it’s just lovely.” And so I bought it.

(Stops, looks at DADDY)

DADDY

(To show he is paying attention)

And so you bought it.

MOMMY

And so I bought it, and I walked out f the store with the hat right on my head, and I ran spang into the chairman of our woman’s club, and she said, “Oh, my dear, isn’t that a lovely little hat? Where did you get that lovely little hat? It’s the loveliest little hat; I’ve always wanted a wheat-colored hat myself.” And, I said, “Why, no, my dear; this hat is beige; beige.” And she laughed and said, “Why no, my dear, that’s a wheat-colored hat . . . wheat. I know beige from wheat.” And I said, “Well, my dear, I know beige from wheat, too.” What did I say? What did I just say?

DADDY

(Tonelessly)

Well, my dear, I know beige from wheat, too.

MOMMY

And I said, “The minute I got outside I could tell that it wasn’t a beige hat at all; it was a wheat hat.” And they said to me, “How could you tell that when you had the hat on the top of your head?” Well, that made me angry, and so I made a scene right there; I screamed as hard as I could; I took my hat off and I threw it down on the counter, and oh, I made a terrible scene. I said, I made a terrible scene.

DADDY

(Snapping to)

Yes . . . yes . . . good for you!

MOMMY

And I made an absolutely terrible scene; and they became frightened, and they said, “Oh, madam; oh, madam.” But I kept right on, and finally they admitted that they might have made a mistake; so they took my hat into the back, and they came out again with a hat that looked exactly like it. I took one look at it, and I said, “This hat is wheat-colored’ wheat.” Well, of course, they said, “Oh, no, madam, this hat is beige; you go outside and see.” So, I went outside, and lo and behold, it was beige. So I bought it.

MRS. BARKER

My brother’s a dear man, and he has a dear little wife, whom he loves, dearly. He loves her so much he just can’t get a sentence out without mentioning her. He wants everybody to know he’s married. He’s really a stickler on that point; he can’t be introduced to anybody and say hello without adding, “Of course, I’m married.” As far as I’m concerned, he’s the chief exponent of Woman Love in this whole country; he’s even been written up in psychiatric journals because of it.

DADDY

Indeed!

MOMMY

Isn’t that lovely.

MRS. BARKER

Oh, I think so. There’s too much woman hatred in this country, and that’s a fact.

GRANDMA

Oh, I don’t know.

MOMMY

Oh, no. No, you must be mistaken. I can’t believe we asked you here to give you any help. With the way taxes are these days, and the way you can’t get satisfaction in ANYTHING . . . no, I don’t believe so.

DADDY

And if you need help . . . why, I should think you’d apply for a Fulbright Scholarship. . . .

MOMMY

And if not that . . . why, then a Guggenheim Fellowship. . . .

GRANDMA

Oh, come on; why not shoot the works and try for the Prix de Rome.

(Under her breath to MOMMY and DADDY)

Beasts!

MRS. BARKER

Oh, what a jolly family. But let me think. I’m knee-deep in work these days; there’s the Ladies’ Auxiliary Air Raid Committee, for one thing; how do you feel about air raids?

MOMMY

Oh, I’d say we’re hostile.

DADDY

Yes, definitely; we’re hostile.

MRS. BARKER

Then, you’ll be no help there. There’s too much hostility in the world these days as it is; but I’ll not badger you!

Anyway . . . have you heard of that big baking contest they run? The one where all the ladies get together in a big barn and bake away?

YOUNG MAN

I’m . . . not . . . sure. . . .

GRANDMA

Not so close. Well, it doesn’t matter whether you’ve heard of it or not. The important thing is—and I don’t want anybody to hear this . . . the folks think I haven’t been out of the house in eight years—the important thing is that I won first prize in that baking contest this year. Oh, it was in all the papers; not under my own name, though. I used a nom de boulangère; I called myself Uncle Henry.

YOUNG MAN

Well, I’m a type.

GRANDMA

Yup; you sure are. Why do you say you’d do anything for money . . . if you don’t mind my being nosy?

YOUNG MAN

No, no. It’s part of the interviews. I’ll be happy to tell you. It’s that I have no talents at all, except what you see . . . my person; my body, my face. In every ther way I am incomplete, and I must therefore . . . compensate.

GRANDMA

What do you mean, incomplete? You look pretty complete to me.

YOUNG MAN

I think I can explain it to you, partially because you’re very old, and very old people have perceptions they keep to themselves, because if they expose them to other people . . . well, you know what ridicule and neglect are.

GRANDMA

I do, child, I do.

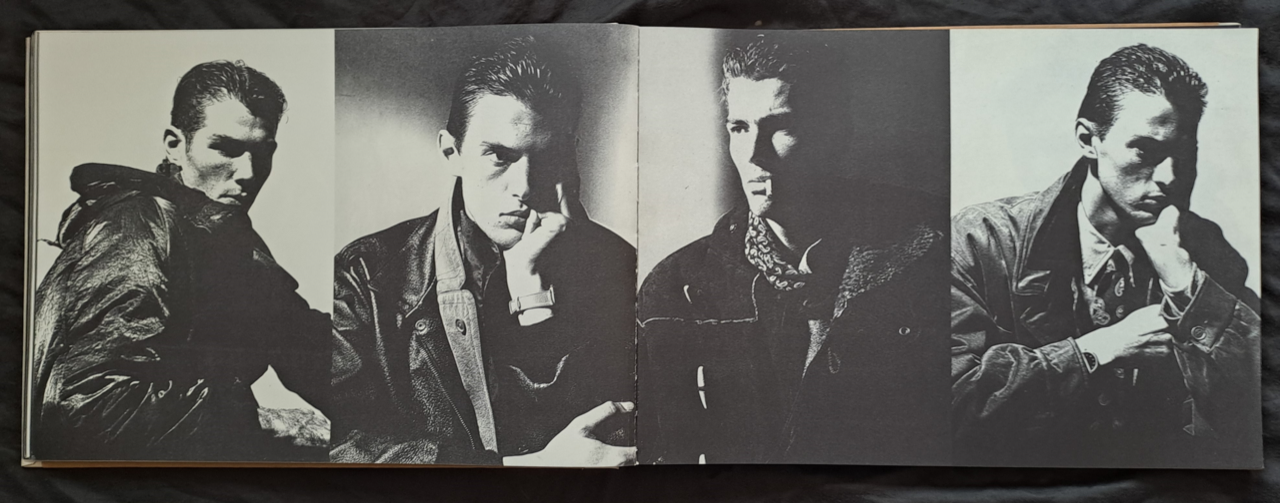

Before they didn’t make anything but clothes for war…

The command centres of the leading nations asked themselves a lot of questions; how can you reach for a round of armour piercing bullets and explosives to blow up a tank when it’s -30 degrees? How can a pocket protect and also allow easy access when your fingers are frozen? Would a hood be able to prevent the men from being dazzled by the light given off when a kiloton bomb explodes? Why can’t a thermal radar detect the infrared reflection from the heat of a commando’s body slipping under barbed wire? Is there a liquid or r component that will make us invisible? Can we send luminescence back to the transmitter? The uniform must be faded like the battlefields. Laboratories that seemed like enormous camouflage factories for bolting oneself to the ground and fading into the landscape. Because the game of war could be exported to out-of-the-way areas; heavenly places, volcanic islets or deserts. These were the questions they posed themselves in the offices of their bunkers.

Then came a generation that experienced Peace. So we returned our war clothes. And twenty years later we let our hair grow and wrote the sign Peace & Love on the backs of our old field jackets fishes back out again from military surplus stores.

you wanted to do everything for your customer, that crazy little man: clothing that reassured him, that told him where he was all the time, allowing him to experience adventure at the wheel of his Four Wheel Drive, mounting the pavement of a piazza designed by Palladio on two wheels, while his telephone told him the date and time, a map, the temperature. What does he want???

You know, you prepared them for the aesthetics of the hell they wanted to live in. You had to have a vision…Malls, which were like the bunkers of previous generations. The destruction of infrastructure, buried deep down (underground factory, headquarters, etc.). Intercontinental missiles able to target the heart of the enemy nation. Nothing has changed. I can only say that I miss you Massimo. And then when it’s no longer possible to breathe outside and everyone will live underground, that then will be the apotheosis. We’ll make self-tanning fabrics in the synthetic light, in the bunkers and the underground shelters where we’ll have learned to live, known now to us as mall or shopping center. You know Massimo, you really were right.

Although textiles are often thought of simply in terms of clothing (first for protection from the elements and later, for purposes of adornment), and in terms of interior decoration, it should not be forgotten that they have also been an essential element of housing, in the form of the tent (on which subject there is a remarkably small literature), and for travel itself, in the form of luggage, and especially, for sails for wind-powered water transportation.

The intimate relationship between textiles and society can also be seen in the fundamental role it played in the rise of the capitalist system, as the first large-scale capitalist industry (the production and export of wool in medieval Flanders); in the industrial revolution (the mechanization of cotton spinning and weaving in eighteenth-century England); in architecture, as the object of the first multi-storied iron frame building (Bage’s flax mill in Schrewsbury, England in 1796); as the subject of the first working-class history (Henson’s history of the framework-knitters in 1831); or as the subject of the first semiotic text (Roland Barthes’ La Mode, Paris 1963); not to mention that the French word for loom is the same as the general word for profession or trade (“métier”), and the German word for textiles is the same as the general word for material or matter (“Stoffe”), which is also the case for the Dutch word “stof”, as well as in English, with the word “material”.

Perhaps it is by chance that Christopher Columbus, like his father, was first a wool weaver and wool merchant, but it is quite logical that the Jacquard loom in early nineteenth-century France was the inspiration for the early work of Charles Babbage in England which lead directly to the invention of the computer in the twentieth century.

Until the fifteenth century, in Europe, the printed literature of textiles is almost entirely limited to passing references to the textile fibers, clothing, and some woven cloth, as textiles were considered as a sub-category of agriculture